Fitness drift

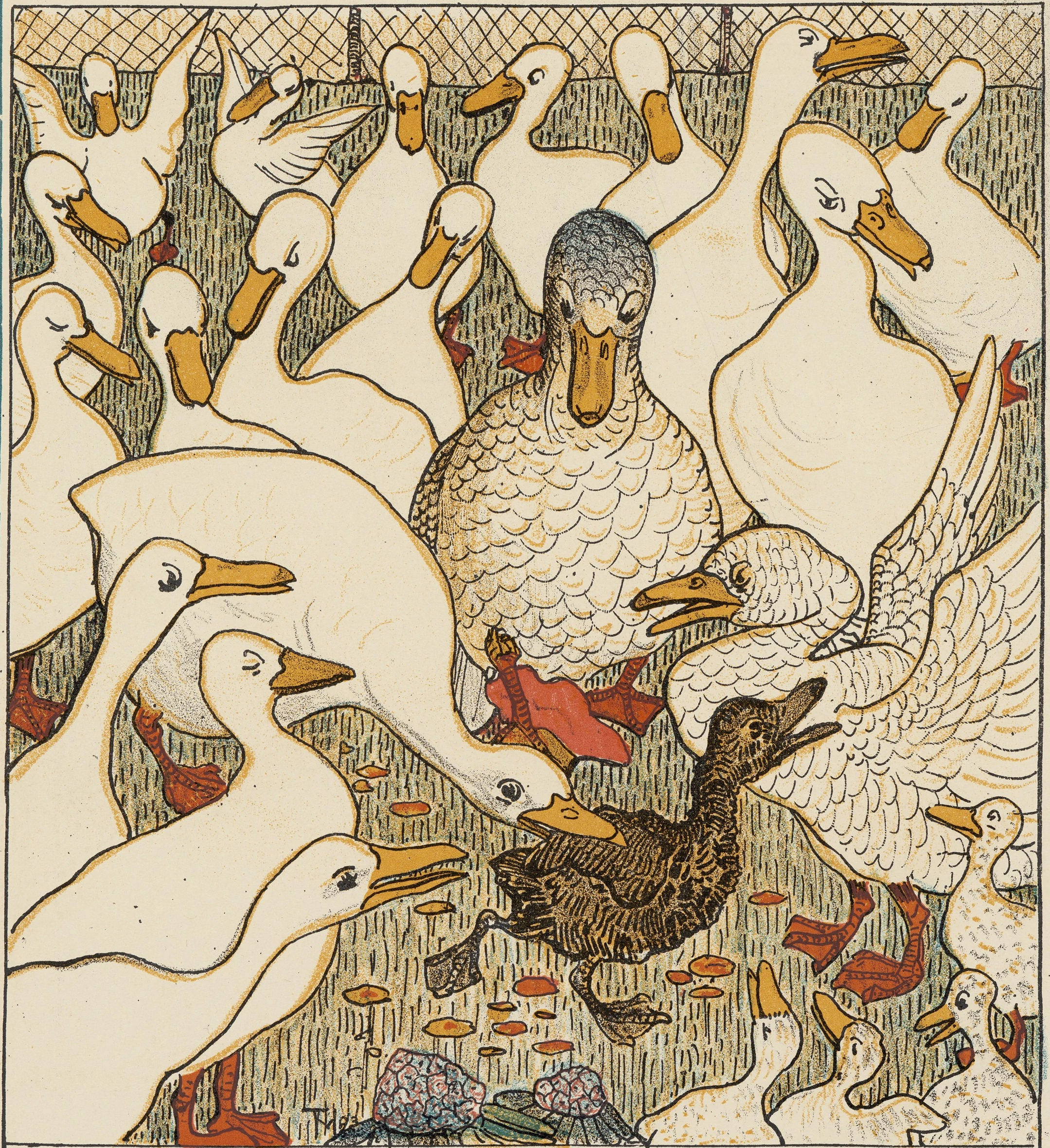

image: The Ugly Duckling, illust. by Theo Van Hoytema (1893)

There may be a moment when your new AI seems to be perfectly trained. You might feel inclined to say “This AI is fit and ready for production! It’s perfectly adapted to the world it needs to deal with. It’s scoring fabulously well on every test we give it.”

Being fit doesn’t last forever. Even a well-trained AI can only be well-trained on the training data fed to it. As the world continues to evolve, unless an AI continues to evolve along with it, the AI will get left behind.

Fitness drift describes what happens when an AI starts to get out of sync with the world it’s supposed to be trained on. Either the world moves along beyond what the AI was trained on, or the AI is modified (due to accident or manipulation) in ways that move it away from fitting in with the world, or both.

The world is full of surprises

Data models and AIs have been used for many years to predict consumer demand and plan industrial capacity. Whether you’re in the travel business, the commercial real estate business, or even in the candy business, predicting the future helps you use capital efficiently, and make wise investment decisions.

Before 2020, all the top companies in these and many other industries used high-scoring well-trained AI models to plan their budgets. Within a few months, it became apparent that none of those models were even remotely applicable to the COVID world we all found ourselves in. When the circumstances are new and different, a high-scoring well-trained AI is pretty much useless.

Practice makes permanent

Repeated exposure is how an AI learns how to classify its inputs. If it sees enough white swans, it’ll start to think that all swans are necessarily white. This is called reinforcement learning. Repetition is what raises a model’s score.

The success criteria for such an AI model is not truth, but rather familiarity. That’s why gargantuan training sets are always in demand. An AI can only get high scores for fitness when every situation it might encounter is one of those that it has been trained on.

If a rare and unforeseen event occurs, the AI has no powers of reason to fall back on. If it sees a black swan1, its training won’t allow it to recognize the input as a swan.

Novelty is not welcome

The Achilles’ heel of a neural network is novelty. When an unfamiliar new input comes along — something that doesn’t appear anywhere in its training set — an AI is trained to reject, not accept it. If the AI accepted the input, filing it into an existing category of known inputs, that would count against it as a false positive. Since it doesn’t fit any of the training data, a black swan event will not fall into one of the model’s pre-existing categories.

So, the first requirement of a well-trained AI is to ensure it rejects patterns that don’t fit the training set. The stronger the rejection, the better the AI’s score.

Some AIs have been trained to produce extremely clever and original solutions to very tough problems. They have surpassed human performance in diverse fields, from playing chess and go to protein folding. Each of these solutions are findable because the problems can be stated in terms of an objective function. This is a stable score that is readily computable and which distinguishes “good” solutions from “bad” ones. But cognition in the real world often does not have a readily computable objective function. AIs do not find solutions when the goals are subjective, and success is not readily computable.

Generative AI is designed to plagiarize and rehash material that it has been given, but what it creates is not original. Originality is a sliding scale, and generative AI tends to work best at the “non-original” end of that scale. It does a great job of drawing faces with different noses (…and only if those noses are supplied as a large facial database). It can’t come up with something wholly original like E=MC2, at least not with any clue as to whether it was true or not. The AI can swap terms around to derive billions of plausible and similar-looking combinations. But it can’t reason, comprehend meaning, or recognize the significance of that equation.

If a signal doesn’t appear in the training set, it will not appear in the output with any significant strength or confidence. This is known as inductive bias: the bias to only accept the patterns from training, as if nothing else matters.

This means that novelty is a frontier for AIs. It sets a distinct limitation on what they are capable of, and that is where we should expect to see its failures.

The engines of confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the essential engine of AI training. The weight given to an outcome that deems it “most likely” doesn’t come from reason, but confirmation bias.

AIs with confirmation bias are also notoriously opaque - decisions are made quickly and confidently, but never justified. The closest you might get to an explanation is a vague indication that some input resembles past inputs. This is of course how prejudice and intolerance work: the only explanation is “everyone just knows this is true.”

So what

You can have AIs that stay fit: these are engines of confirmation bias which fail to recognize novelty and originality, and select for endless repetition of the past.

Or you can have AIs that drift from the world that they’re supposed to model: these increasingly produce more and more errors in the form of false positives and false negatives.

We install AIs into industry and government, giving them power and authority to make decisions that affect our lives. When AIs are trusted to make decisions that affect our lives, we must struggle to remember that they do not handle novel situations well.

When those decisions affect our lives, we should remember these AIs are the engines of intolerance for those of us who are, like the Ugly Duckling, just a little different.

-

Nassim Nicholas Taleb. The Black Swan. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2010. ↩